I spent a lovely evening with my son at a gardening class a few nights ago. It would have been cheaper to take him out drinking. We’d at least have payback from the empties, unlike what I’ll get when these plants follow the proud tradition of those who have been potted before them, which is up and die.

What won’t die this time, though, are the memories of his patience as I listened to the gardener speak plainly and slowly, then tried to translate his simple commands into visible action. An entire greenhouse at my disposal with any plant I wanted to use (and buy, of course). Helpful staff. A warm, pleasant evening. All odds were in my favour but still, my project looked like a reject from toddler day at the flower show. “No, your container doesn’t look like hers,” my son murmurs in a tone surprisingly mature for 14, “but that doesn’t me an it’s ugly.” He pats my hand and points to a bench bursting with blooms. “Here, try these.”

Selecting five random plants, he trowels, inserts, tamps down, and waters, his sturdy 6-foot frame curled over my container like Merlin in his quest for gold. Standing tall to reveal his work, the mixed blooms blend into a floral family right before my eyes.

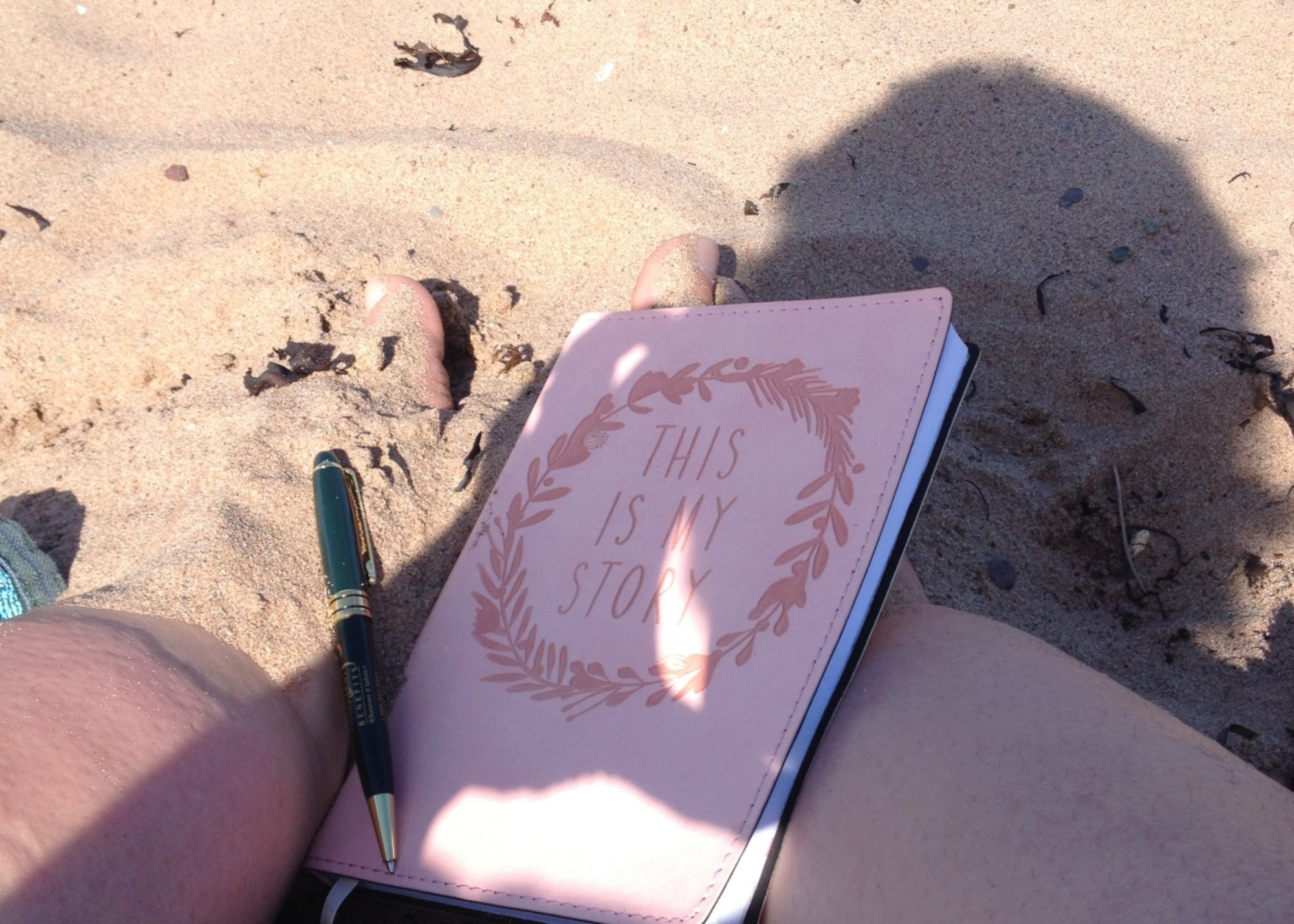

Like the chapters in my books. At first, I love them, the idea, the flow. Then I hate them. Everyone else’s books read better, sound better, sell better. I push back from the keyboard in resigned exasperation. I sow hopelessness and resignation under a thick layer of gloom upon all with the misfortune to cross my path. Then someone comes along and calms me down with a focused dose of reality. Sometimes, it is my muse. Or a child whispering “I love you, Mommy, even though your books don’t sell.” Or an angel bearing Margaritas. Whatever the wakeup call, I squint in the newfound sun and in the immortal words of my great-grandmother, I get over myself, go back to my screen and keep going. It doesn’t sound like their stories because it is mine, flaws and gaps and all.

And in the fading glow of the evening sun, I listen to my son, not bearing Margaritas but marigolds, amid words for which my frustration is no match.

No, my container doesn’t look like hers. But it is still beautiful.

His talent does not go unrecognized. His glow of pride as his container is complimented by passing staff and gardeners is outshone only by the glow of my credit card as it bears the pressure of tuition, soil, baskets, and plants with names straight from outer space and pedigrees to match, given the price of the little darlings. But even if I kill every last one, the money spent will pale to the memory no one can erase, dismember or otherwise take away. How often does a teen want to hang with his mom? There’s the priceless gem.

There’s one in every torment, waiting for those willing to dig in the dirt and bring it to light.